By Joshua Ozugbakun & Emerald Awa-Agwu

In July 2016, after over two years of being polio-free, two wild poliovirus cases were discovered in Borno State, Nigeria. This launched fresh efforts to strengthen the four pillars of polio eradication including Routine Immunization (RI), Supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) (including national Immunization Plus Days (IPDs)), Surveillance and targeted mop-up campaigns.

A health worker vaccinates a child with the Oral Polio Vaccine

Partners, both local and international, collaborated with the Nigerian government at state and national level, through various interventions and projects to increase the coverage and effectiveness of IPDs and mop-up campaigns in order to increase herd immunity and stop polio transmission, especially in high-risk states like Adamawa, Borno and Yobe states. These interventions were coordinated by the State Emergency Routine Immunization Coordination Centers (SERICCs). Each SERICC is led by individual state governments and help to improve information sharing, joint programming of public health emergency management activities (planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation) with partners. The National Emergency Routine Immunization Coordination Center (NERICC) is responsible for strategy development and oversees the activities of all the SERICCs. With this coordination mechanism in place, the menace of polio is being tackled collaboratively and Nigeria is well underway to being declared ‘Polio Free’, a major milestone in its vaccine-preventable disease management efforts.

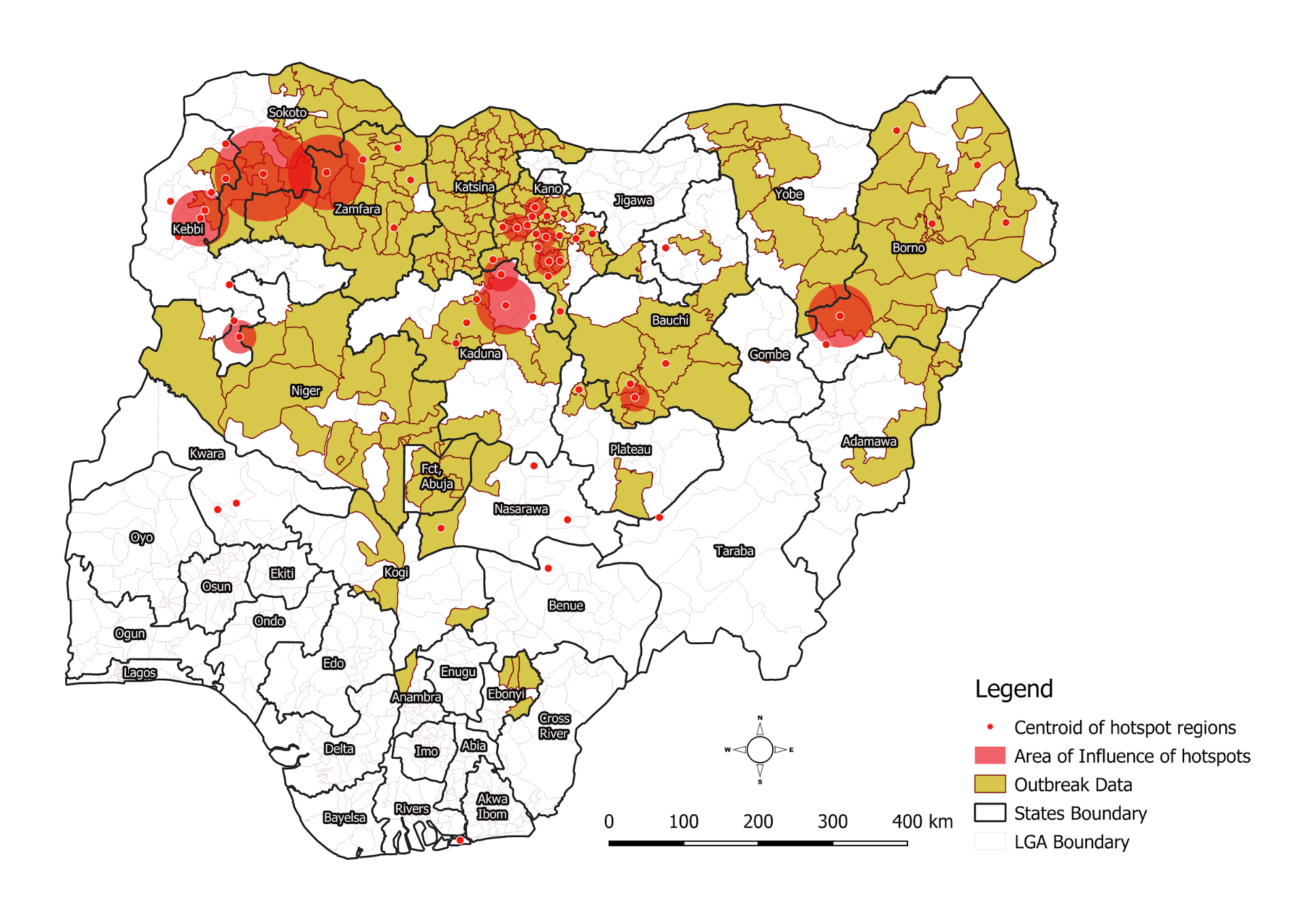

A major takeaway for Nigerian polio eradication stakeholders after years of battling polio is the need for data collection, management and storage systems to be upgraded. As the need to halt poliovirus transmission increased, it became increasingly obvious that paper-based data management systems were incapable of providing decision makers with the reliable, actionable data which they needed for effective programming. eHealth Africa responded to this challenge by supporting states across Nigeria to develop comprehensive, digital maps using our expertise in Geographic Information Systems (GIS). The accuracy of these maps improves the microplanning process and guarantees a greater coverage of settlements during campaigns.

Our GIS technology has improved the quality of maps used for polio campaign planning

In addition, through our Vaccinator Tracking Systems (VTS) project, GIS-encoded Android phones are used to record and store passive tracks of vaccinators as they conduct their house-to-house visits; allowing decision-makers to have an accurate picture of the settlements that have been covered during IPDS and mop-up campaigns. This data can easily be accessed through dashboards for a more detailed analysis and breakdown of coverage information.

Supporting polio emergency response activities also highlighted the need for the Nigerian health system to move from an emphasis on SIAs and campaigns to strengthening the RI and disease surveillance systems. Sound routine immunization and disease surveillance systems are necessary to sustain the herd immunity built through polio campaigns.

In Kano state, the LoMIS Stock solution helps the State Primary Health Care Management Board to ensure that the vaccine supply chain is maintained. Health workers at the facility level use the LoMIS Stock application to send reports on a variety of vaccine stock indicators including vaccine utilization, vaccine potency, stock levels, wastage rates, and cold chain equipment status. Supervisors access the reports through the LoMIS Stock dashboard and are able to respond appropriately. This ensures that the RI system is maintained and that health facilities are never out of stock.

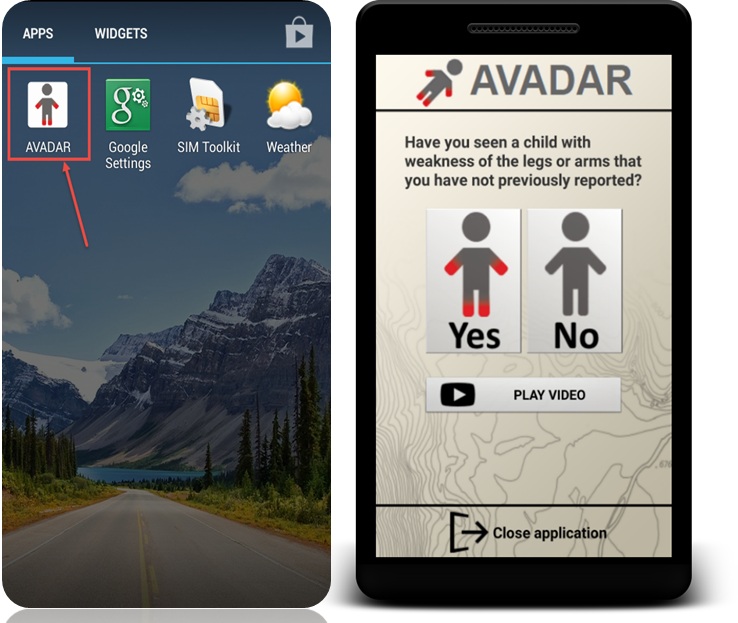

In the past, Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) surveillance in health systems across Africa was passive. This meant that disease surveillance and notification officers (DSNOs) only reported or investigated suspected AFP cases that were presented at the health facility. According to the U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)1, over 72% of polio cases are asymptomatic and as such, will not present at the health facility. In addition, DSNOs are unable to visit every single community to actively search for AFP cases due to logistics and security challenges. Relying on data from passive AFP surveillance causes programs to be designed based on data that excludes the asymptomatic polio cases. Auto-Visual AFP Detection and Reporting (AVADAR) reduces the burden on the DSNOs by enlisting members of the community to actively find AFP cases and report using a mobile application on a weekly basis; thus, providing accurate real-time surveillance data that can be used for program planning and implementation.

An often overlooked factor that promoted the transmission of the poliovirus was the rejection of the polio vaccine by mothers and households due to various myths and socio-cultural barriers. By engaging traditional and religious leaders as ambassadors of vaccination, more mothers and households are accepting the polio virus.

The central lesson in Nigeria’s journey so far towards polio eradication is the importance of collaboration and engagement at all levels including communities. eHealth Africa is proud to be supporting governments and health systems across Africa to respond to the polio emergency.